FILM COMMENT, A. S. Hamrah

Consider this an afterword to Taste of Cherry (1997), the feature that brought its director, Abbas Kiarostami, to full international prominence, after it became the first Iranian movie to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival (where it shared the prize with The Eel, by Shohei Imamura). It is best to see Taste of Cherry without reading anything about it first. It should be seen cold—cold like the ground into which the film’s protagonist, Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), seeks to consign himself.

Taste of Cherry uses the cinema to figure out if life is worth living, a hard question that seems superficial because so many films so easily reach the conclusion that it is. They show us a wedding, a happy family, a good job, a lottery winner. They indulge our desire to see things work out for the best. Kiarostami does none of that. Taste of Cherry excludes, cutting away plot and backstory, two things that can bog down a film. It goes in circles and meanders, the concision of its ninety-nine minutes becoming clear only in retrospect. It is meant to conceal, even to frustrate. Instead of tying the story up neatly, its ending does something else.

Kiarostami’s unexpected death in a Paris hospital in the summer of 2016, at age seventy-six, was a blow to cinephiles all over the world. It took a while for us to recover. A retrospective of his films traveled the United States in 2019, providing a much-needed summation of his career, which had started with 1970’s Bread and Alley, the first of many films he made for Tehran’s state-run Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults. Over the course of the decades that followed, he became the cinema’s great poet of the ordinary and the everyday, of the unnoticed.

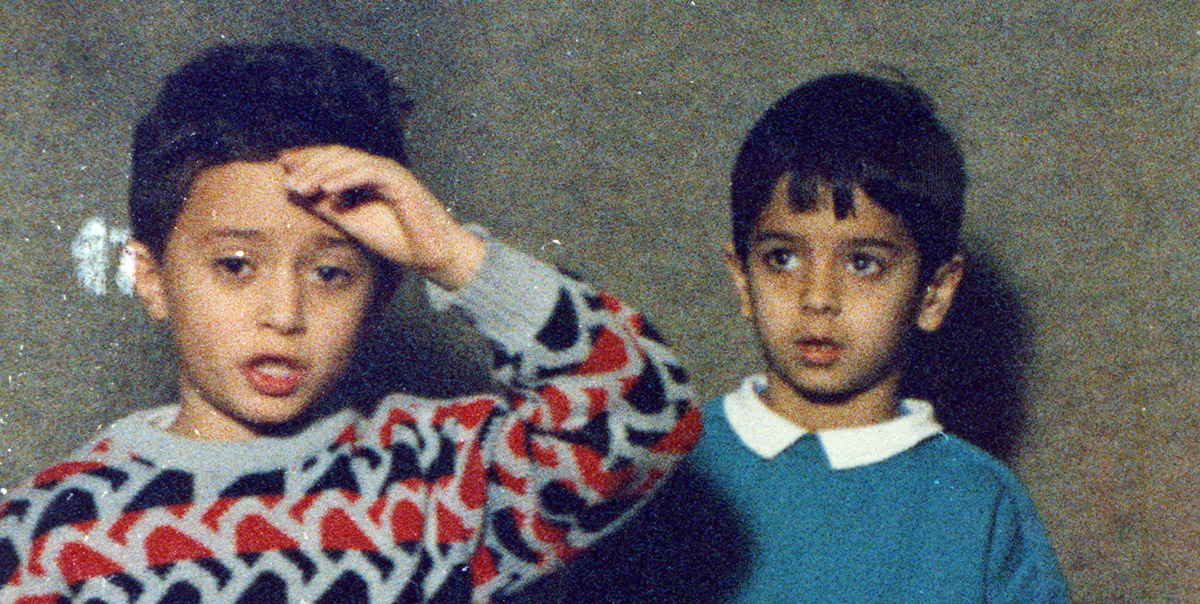

Kiarostami’s films portray friendship and its difficulties, its fragility and uncertainty. Nowhere is that more striking than in Homework (1989), which begins as a documentary about schoolboys who haven’t finished their homework, then proceeds through a series of interviews in which students face Kiarostami’s camera alone to discuss their fraught relationships with their parents. Near the film’s end, a boy named Majid becomes paralyzed in front of Kiarostami, unable to speak, distraught that he can’t be interviewed accompanied by his friend Molai. Majid’s anguish is wrenching and difficult to watch. Kiarostami records this child’s breakdown, then the calming effect Molai has on him, in a way that suggests Majid’s pain is a problem larger than just one boy’s anxiety. The children in Homework are growing up neglected by their parents and teachers, who are quick to punish and unconcerned about nurturing them as fellow human beings.

By the nineties, Kiarostami had begun to complicate human relationships further, by folding and refolding them into issues of cinematic representation and narrative ambiguity. In Close-up (1990)—the true story of a man (Hossein Sabzian) who plays himself as the impostor he was—the yearning for human connection comes to the fore in new ways.

After Kiarostami's death, Mohsen Makhmalbaf—his fellow member of what is sometimes called the Iranian New Wave, who in Close-up plays himself, the filmmaker whom Sabzian was arrested for impersonating—summed up his colleague’s life and career for the BBC: “He could show you how friendship could take you out of loneliness.” The title of the 1987 film that begins the director’s Koker Trilogy asks the main Kiarostamian question: Where Is the Friend’s House? The following two films in the trilogy, And Life Goes On (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994), take place in the aftermath of the devastating 1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake. Those films put Kiarostami on the road to Taste of Cherry, in which he examines the precariousness of life without the backdrop of natural disaster. In Taste of Cherry, the calamity is private and subjective. We are never told what it is. Perhaps it is life itself.

• • •

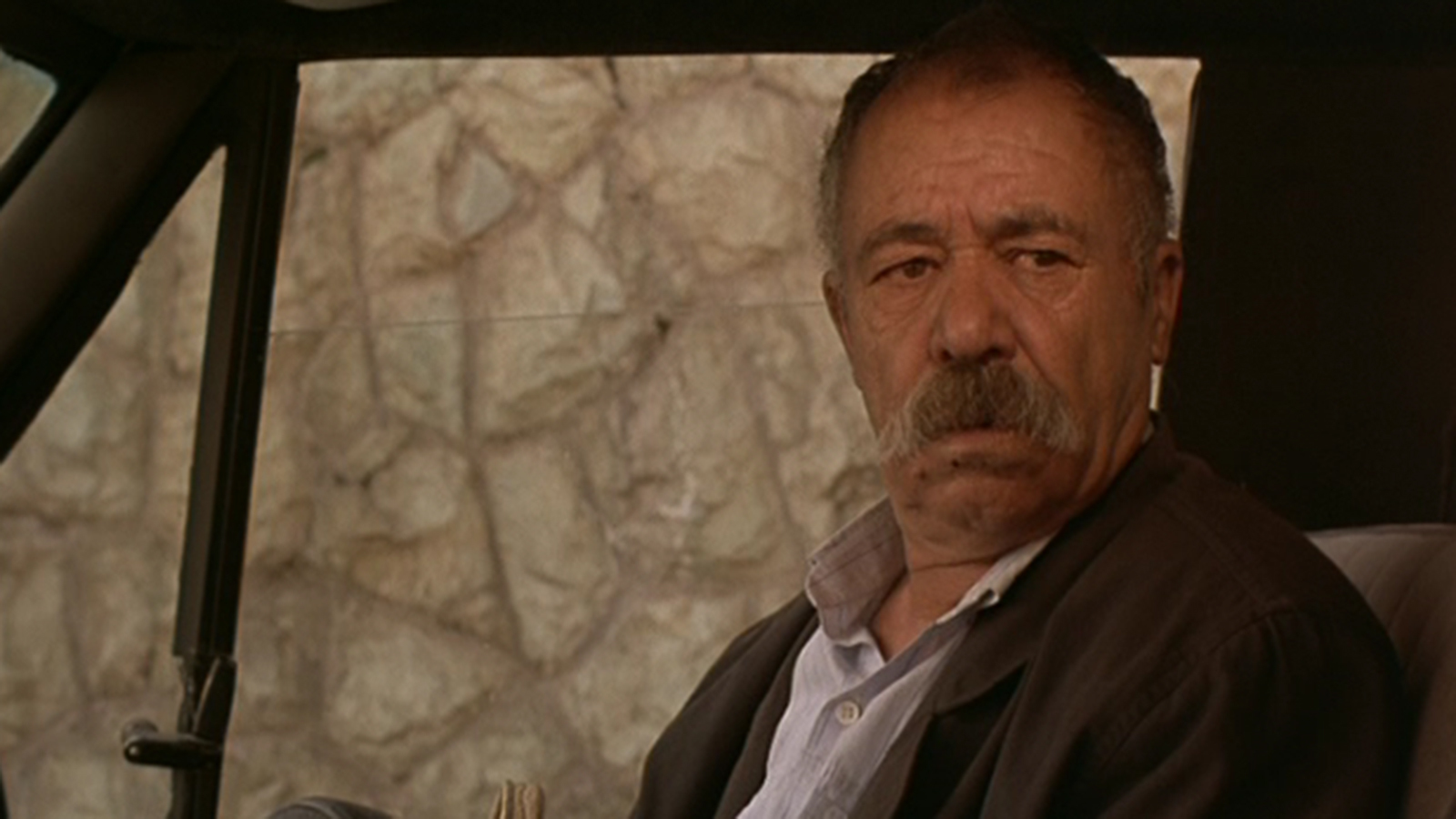

Mr. Badii keeps asking strangers if they are his friends, or if he is their friend, because he wants to find someone who will aid him in his suicide, first by confirming that he has succeeded in killing himself, then by burying his body in the event that he has. Jonathan Rosenbaum, one of the great explicators of Kiarostami’s work, notes how the director’s films—often featuring nonprofessional actors, and fusing fiction and documentary—frequently depict the “strained interactions between big-city protagonists and the impoverished yet [to them] exotic villagers they’re visiting,” as is the case here. The cosmopolitan Mr. Badii drives around the outskirts of Tehran, soliciting assistance from a soldier, a seminary student, and a taxidermist.

What Badii asks the men he meets to do is to permanently end a human connection, not create a new one. He wants them to help him commit an act that will lead to secrecy and guilt on their part, and one that is, furthermore, against Islamic law. In Taste of Cherry, each character becomes uneasy or threatening as Badii tries to cajole him with money, rather than with the kind of fleeting intimacy that comes from helping strangers.

In leaving out any reason for why Mr. Badii has reached this point—something that would usually be considered essential in a film about a suicidal man—Kiarostami subverts and undercuts his protagonist’s talk of friendship. When Badii explains that he is “simply asking for a helping hand” while insisting that he can’t say why because “it wouldn’t help you to know,” he is already severing himself from other people.

“You can’t feel what I feel,” the only explanation Badii is willing to offer, similarly challenges the movie itself. If no one can feel what others experience, then there is no point in watching. Badii’s hesitations, the distress in his eyes, performed by Ershadi with restraint or reluctance, belie what he is saying, the same way certain actions and casual comments inadvertently reveal his will to live. He lets road workers help him get his Range Rover out of a rut on the side of a hill over which he could have plunged to his death. He refuses an offer of an omelet because “eggs are bad for me.”

• • •

With his prominent nose, dimpled chin, stubble, and dark lips closed to match his stern, straight-ahead stare as he drives, Ershadi’s right profile is the image that holds the film together. Kiarostami, in fact, had first spotted Ershadi, a Tehrani architect, driving one day. He stopped him and asked if he would appear in a film. Ershadi has since acted in other movies, but because he was new to the cinema in Taste of Cherry, his presence will always carry with it the permanent mystery of Badii’s motivation.

It is only about two-thirds of the way in, when the gruff museum taxidermist (Abdol Hossein Bagheri) asks Badii if he is willing to give up the taste of cherries, that we see women in this film, in long shot: a mother and daughter on a roof, taking laundry off a line. Shortly after this, outside the Darabad Museum of Natural History, a young woman hands Badii a camera and asks him to take a photo of her and her boyfriend. The boyfriend appears to be a man from the beginning of the film who threatened to punch Badii in the face when he offered him money, assuming Badii was propositioning him for sex.

• • •

In his one-star pan of Taste of Cherry from 1998, when the film was released in the U.S., Roger Ebert accuses Kiarostami of prurience for the movie’s early sections, in which Badii’s intentions are made purposefully unclear as he asks various men on the sidewalk for help from his car. Ebert calls the film “a lifeless drone,” comparing it unfavorably to a 1992 Ulrike Ottinger movie: “I have abundant patience with long, slow films, if they engage me. I fondly recall Taiga, the eight-hour documentary about the yurt-dwelling nomads of Outer Mongolia.” He concludes by declaring that Taste of Cherry is not worth seeing.

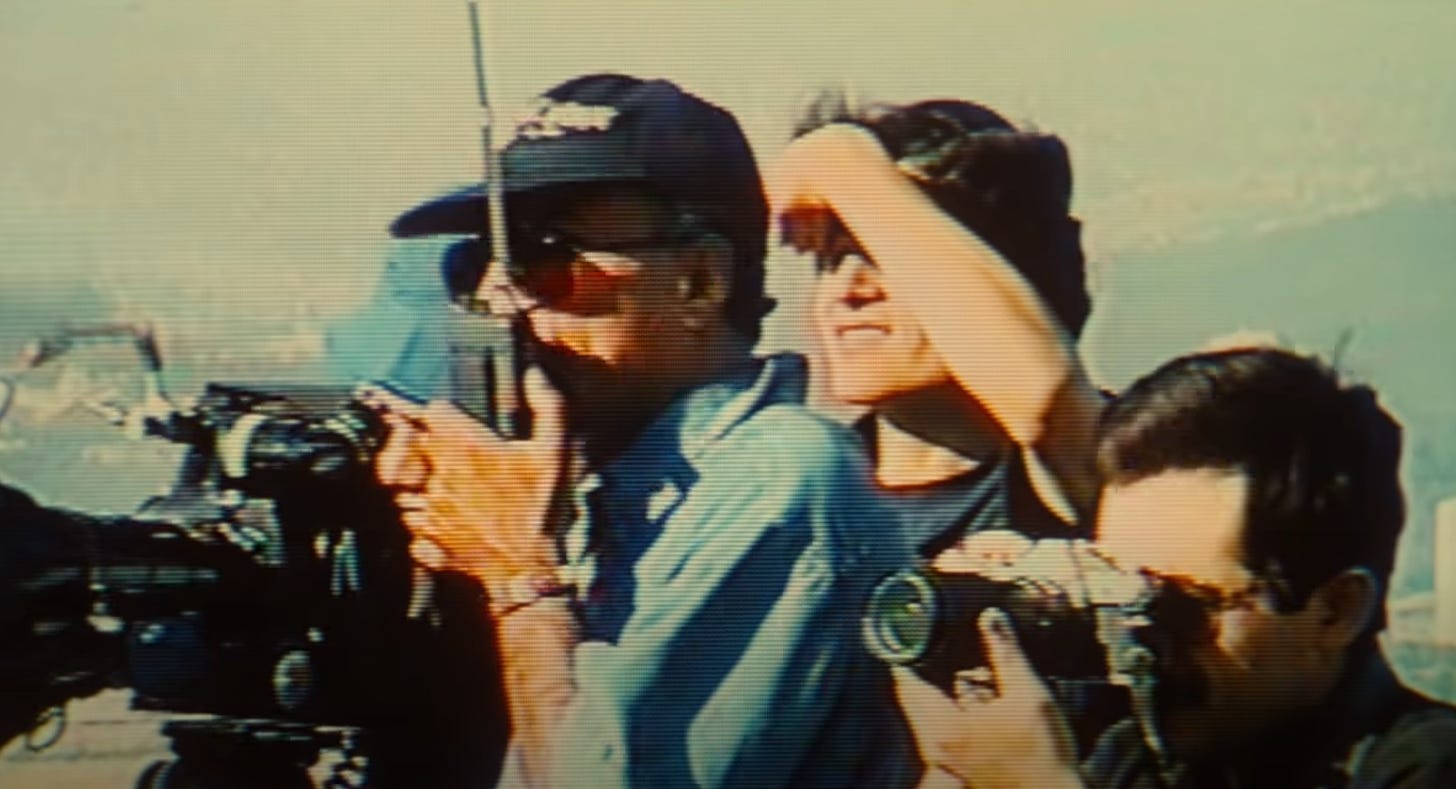

Ebert also describes the film’s ending as “a tiresome distancing strategy to remind us we are seeing a movie.” It is, in fact, quite the opposite. As Badii lies down in his grave, we see the full moon shrouded by black clouds—maybe the best image of the moon in cinema, and maybe the last thing Mr. Badii will ever see. After turning the camera back on Badii, as he gazes up at a gathering storm, Kiarostami fades in on video footage of soldiers marching up a hill in long shot. He then cuts to scenes of the crew at work on the film—including Ershadi, who smokes and offers Kiarostami a cigarette—soon accompanied by Louis Armstrong’s 1928 recording of “St. James Infirmary,” a song heard nowhere else in this film that is otherwise without a score or any nondiegetic music on the soundtrack. The graininess of this video footage transferred to film, the brightness of the sunny day, and the ease and friendliness of the film’s cast and crew contrast sharply with Badii’s dark night of the soul. This ending—so unexpected, because what film has ever ended like this?—seems at first like a mix-up.

There is no definitive explanation for this break in the narrative. It is several things at once: a scene of mournful tranquility, a contemplation of the happiness of being alive, relief from the film’s tension, a rejection of sentimentality, a moment of rebirth, and an invitation to leave the theater. Above all, it is a memento mori that deepens the film’s ambiguity, the final fate of Badii having been left unresolved. If, after this film’s ninety-nine minutes, neither we nor Mr. Badii have come to know whether life is worth living, so be it.

---------

I’ve been thinking a lot about the “message” of this movie, of course. Is it pro-suicide or pro-life? What happens to Mr. Badii in the end and does it even matter? What to make of the final scene of the crew filming?

Ultimately, I can see how this movie could be read as pro-suicide. It’s safe to assume that Mr. Badii does die in the end and is buried with the help of another person. It can also be assumed that we are expected to sympathize with the main character and his desire to die and even think he made some good points about his right to do so. I actually think this is incredibly powerful and important, to give a raw and genuine voice to those struggling with thoughts of suicide.

But it also says a lot that the last man to talk with Mr. Badii, Mr. Bagheri, was opposed to suicide. He talked mostly about life and all the things to be missed: the mulberries, the sunsets, the sounds of laughter. He’d been to the edge of wanting to die and was able to come back from it. Yeah, he agreed to help Mr. Badii, but he was also using the money to help his sick son, so he was still on the side of life. And yeah, his advice was basically the modern equivalent of toxic positivity, but he was, I think, doing his best to tether Mr. Badii to the world he saw. A man who left his house wanting to die and came back with mulberries is, I think, the loudest voice Kiarostami wants us to hear.