For two decades after its making, Edward Yang’s magisterial A Brighter Summer Day was more an alluring legend than a known presence for American cinephiles. Passed over by festivals, including Cannes and New York, after its completion in 1991, the four-hour film gradually began to circulate in specialized venues and among critics, with the result that it was named one of the most important films of the nineties in polls at the decade’s end. Yet it was only with its first, limited U.S. theatrical run in 2011, following a restoration by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation, that it was widely hailed as a masterpiece of modern cinema as well as a defining work of the New Taiwan Cinema, which enjoyed a decade-long flowering beginning in the early eighties.

Though now decades old, Yang’s fourth feature retains an inexhaustible freshness that speaks to viewers the world over. Like a Taiwanese Rebel Without a Cause made with the gravity and epic sweep of The Godfather, the film, which has more than a hundred speaking parts, is above all a vision, in terms of both place and time. The place is Taipei, Yang’s home and the setting and subject of all seven of his features. As for time, we might consider two meanings. The years depicted are 1960–61, a particular juncture in modern Taiwanese history. But the time we witness is also that of adolescence, with all its inner turmoil, outer self-consciousness, and obsessive quest for identity.

For non-Taiwanese viewers, the world Yang conjures can have the paradoxical effect of seeming foreign yet also oddly familiar. Surely the anxieties and confusions of youth give it universal emotional touchstones. Yet, especially for viewers who recall the Eisenhower/

Kennedy era, there’s also an almost dreamlike uncanniness to the ways Yang summons a time when surly young rebels were wild for American rock and roll, Japanese comic books, and John Wayne movies. Perhaps more vividly than any other movie, A Brighter Summer Day immortalizes the moment when teen pop culture went global, forging an effervescent but lasting bridge between East and West.

Yang centers his film on a fourteen-year-old protagonist, Xiao Si’r (a nickname that means “Little Four,” signifying that he is the fourth of five children; his real name is Zhang Zhen, the same as the actor playing him, although the actor’s name is typically spelled Chang Chen in the West). Throughout, the story switches back and forth between the two worlds the boy inhabits: the realm of family and that of school and youth gangs. The film’s first scenes introduce this alternation. In the opening prologue (set in the summer of 1959), we see Xiao Si’r’s father (Zhang Guozhu) pleading with an offscreen school administrator about his son’s bad grades, which have resulted in the boy’s being assigned to an unprestigious night school the following year. Soon after, in a shop on their way home, boy and father listen silently as the names of current school graduates are read over the radio—a reminder of the importance placed on education in this Confucian society, and a litany that will have a melancholy echo in the film’s final scene.

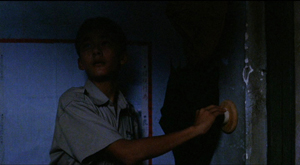

Then it’s the next school year, but rather than being in class, Xiao Si’r and his best friend, Cat (Wong Chi-zan), are high in the rafters of a nearby movie studio, watching a scene being filmed. After a guard appears and forces the boys into a pell-mell chase, Xiao Si’r swipes his large flashlight, which he and Cat, after escaping the premises, use to briefly glimpse two smooching lovers whose identities remain unclear and, in an unexpected way, crucial through much of the story’s remainder.

The motif of light and questions of identity continue to intertwine thereafter. Yang said that one of his chief memories of the period depicted in A Brighter Summer Day was of the spotty electricity and resulting periods of little or no light. That stolen flashlight reappears throughout the story, its use alternately aggressive and defensive. Yet perhaps the most subtly potent effect of the film’s variegated lighting is the way it allows the director’s gaze to lead ours into the chiaroscuro of a haunted past, whose images come at us with the glancing mystery of dreams.

Yang’s bygone Taipei is a zone of disquiet both culturally and politically. Taiwan had been ruled by Japan for a half century before being ceded to China at the end of World War II. Thereafter, the victory of Mao Zedong’s Communists on the mainland led to the invasion of the island in 1949 by the defeated Chiang Kai-shek and his nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party, which then ruled as a military dictatorship until the late 1980s (when new freedoms allowed the greater historical frankness of this film and Hou Hsiao-hsien’s 1989 A City of Sadness). Called the Republic of China, Taiwan under the KMT was allied with the United States, which recognized the regime as the legitimate government of China until 1979.

The new Taiwanese of this KMT era lived a mentally divided existence, trying to adapt to their adopted home while for many years also expecting to return to China once the Communists were vanquished. The kids and families in A Brighter Summer Day are mostly transplanted mainlanders (like Yang, who was born in southern China in 1947 and brought to Taiwan as a toddler). Their culture is traditional Chinese, but it’s framed by that of the native Taiwanese, who speak their own dialect, and by the lingering Japanese influence.

There are other cultural influences at work in Xiao Si’r’s household as well. His parents met in Shanghai (they speak Shanghainese when they don’t want to be understood by their Mandarin-speaking kids) and still retain a number of their pre-1949 connections, some of which will prove problematic for Mr. Zhang, a midlevel functionary in the Confucian mold. His wife (Elaine Jin), a teacher, is a Christian, as is the second of the family’s three daughters. Xiao Si’r also has an older brother, Lao Er (“Big Two,” a nickname that can be pronounced to mean “prick,” a source of recurring jokes), whose gambling debts get him into familial hot water.

If Xiao Si’r is poker-faced and withdrawn at home, in archetypal teenage fashion, at school he’s part of a roiling set of khaki-clad boys with nicknames such as Airplane, Tiger, Sex Bomb, and Deuce. Awash in Western and Japanese pop culture, the kids obey their teachers with grim acquiescence in the classroom, but there’s tension and the hint of violence at every turn; at one point, the school bans baseball bats due to their use as weapons.

Violence is also in the air because of the rivalry between two gangs that many of the boys belong to, each with its own turf, social background, and de facto headquarters. The Little Park Gang, descendants of mainland civil servants, congregates at a brightly lit, American Graffiti–style ice cream parlor, where the diminutive, Elvis-worshipping Cat sings the falsetto parts in American rock-and-roll songs with his band. The 217s, sons of mainland military personnel, hang out at a pool hall, the same one where Lao Er accrues his debts. Though he’s closer to the Little Park crew, Xiao Si’r belongs to neither gang.

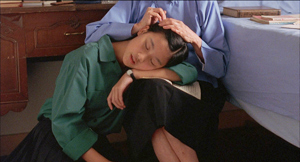

He is drawn toward their antagonisms, though, by a fledgling romantic attraction, and there is nothing anomalous in this: for the boys in A Brighter Summer Day, girls are commodities to be claimed, passed around, fought over. Xiao Si’r’s troubles begin innocently enough. He’s in the school infirmary when he’s asked to escort a fellow student, a girl named Ming (Lisa Yang), back to class. They play hooky instead. At this point, Xiao Si’r may already be in the first stages of a crush, but he knows not to let it carry him away: Ming is Honey’s girl.

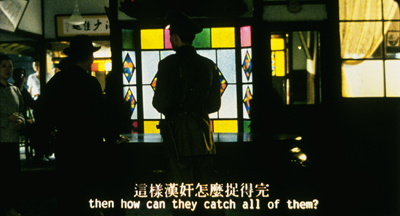

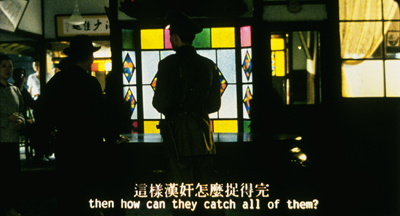

For a long while, Honey isn’t so much a person as a phantom, a legend. He was the leader of the Little Park Gang but killed one of the 217s—supposedly in a fight over Ming—then went into hiding in southern Taiwan. In his absence, the gang is being led by Sly, his aptly named lieutenant, who’s undercutting Honey’s rule in various ways, including by striking a peace accord with the 217s that will allow the two gangs to mount a rock concert together.

Then one day, as Xiao Si’r and Ming exchange shy smiles in the ice cream parlor, Honey suddenly reappears, resplendent in the naval uniform he’s been using as a disguise, and the stage is set for three bravura sequences that compose the midfilm crescendo of A Brighter Summer Day. In the first, Honey, while seeming to “bequeath” Ming to Xiao S’ir, speaks of his life in terms of his favorite novel, War and Peace. In the second, the two gangs stage their rock show, but a challenge to their authority ends in a murder outside the concert hall. In the third sequence, revenge for that death is wreaked during a fierce typhoon, when a Taiwanese gang that had been allied with Honey swoops down on the 217s, resulting in a slaughter that we experience mostly as screams and clatter—the only illumination comes from candles, a careening lightbulb, and that flashlight.

The sequence just described, like the one that follows it, can provoke certain confusions in viewers. Who is attacking whom in this violent and cacophonous confrontation? It’s unclear, not only because of the darkness and rapid editing but also because we’ve not gotten to know the Taiwanese assailants, who are older criminals rather than school-age delinquents. If the film’s writers purposely left these characters shadowy and mysterious, it could be that their decision owed something to the example of Yang’s great contemporary Hou Hsiao-hsien, whose A City of Sadness, released two years before A Brighter Summer Day, evidenced a deliberate strategy of narrative opacity that included leaving certain key information and relationships unexplained.

Hou’s example might also be detected in the film’s visual style, which doesn’t resemble that of any other Yang work. With its concentration of long shots, avoidance of close-ups, repeated compositions in certain settings (especially in the Zhang home), use of doors and windows as framing (and obscuring) devices, and naturalistic lighting, the film recalls Hou’s A Time to Live, a Time to Die (1985) and The Puppetmaster (1993). Critics have seen in these the deliberate articulation of a Chinese or Asian cinematic style derived from models in Chinese literature and visual arts, as well as the work of Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu. Hou has responded that his style’s genesis lay in very practical matters of shooting, and Yang said the same of A Brighter Summer Day. Yet these films undeniably share a visual mood that’s contemplative and beautifully nuanced.

Another anomaly comes in a moment just after the cataclysm of gang violence: the story shifts to the Zhang home, where the secret police arrive and haul away Xiao Si’r’s father for a lengthy interrogation over his past political associations. Why does the narrative make this sudden jump, such that we never see the consequences of the big slaughter we’ve just witnessed? One answer may be that, while the paroxysm of violence gives us a vivid symbol of Xiao Si’r’s psychic turmoil (just as it anticipates a more intimate outburst later), the scenes that follow invoke the film’s more explicitly autobiographical, and historical, underpinnings: Yang’s father was subjected to a similar humiliation, with the result that he left Taiwan on the day he retired, never to return.

This split suggests that A Brighter Summer Day has, in effect, two faces, just as it has two titles. The “outward” face is a highly critical view of a society in which all proper authority—a very Confucian concern—has been eroded or undermined, so that a young man like Xiao Si’r can be hurled into the spiral of violence indicated by the film’s Chinese title, which translates as “The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street,” referring to a notorious crime that inspired the film. The “inward” face, meanwhile, indicated by the lyrics of the 1960 Elvis Presley hit “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” which gives the film its English title, has little to do with Taiwan and much to do with a condition unbound by time or place: the loneliness, melancholy, and longing of adolescence.

DAVID BORDWELLA Brighter Summer Day began as an independent production. Eventually, as Yang’s world expanded, outside funding was necessary to keep the production going. Over half the cast and crew had never worked on a film before, and the project took three years to complete. At a period when the Taiwanese film industry was virtually dead, Yang managed to mount a film of stunning ambition.

Although it was shot as a theatrical feature, it fits surprisingly well into today’s taste for long-form TV narratives. With over eighty speaking parts, it’s a very thick slice of life from 1960 Taipei. Indeed, Tony Rayns’ commentary reports that Yang said he had developed enough story material for three hundred TV episodes. If you like soaking in a richly realized world, here’s a movie made for you.

At the center stands Xiao Si’r, a fourteen-year-old boy having trouble in school. He tries to keep his distance from street-gang culture, but he becomes involved with turf wars while hanging out with his buddies. Si’r also attaches himself to the enigmatic schoolgirl Ming, who is pledged to a gang leader in hiding. A couple of his friends want to sing covers of rock-and-roll hits (most memorably Elvis’ “Are you lonesome tonight?,” the source of the English title). Yang has said that Americans don’t realize the subversive force of pop music in Taiwanese culture. “These songs made us think of freedom.”

To an extent, A Brighter Summer Day can be seen as an alienated-youth, juvenile-delinquent movie, complete with rumbles, tests of loyalty, and confrontations in pool halls and pop concerts. But Yang spreads his canvas in all directions. In the film’s second half, Si’r’s father, a nondescript bureaucrat, falls under suspicion as a political undesirable. That enables Yang to develop parallels between father and son, both stubbornly resisting authority. Meanwhile, the Zhang mother and older sister try to keep the family going in the face of overwhelming problems of school, home life, and political repression.

Widening the lens still further, Yang shows their neighborhood torn by tensions of class, job status, and ethnic identity. Jammed side by side are native Taiwanese families, mainland Chinese of long standing, and recent mainland arrivals who have fled the Civil War of 1946-49. Some families are quite poor, others lower middle-class, and others, such as those of military lineage, fairly well-to-do. The gang rivalries and the adult cliques replicate in miniature these splits and resentments. And the neighborhood plays host to a film studio, which the high-school boys invade in their off hours.

Across the months that the action consumes, the film depicts dozens of character vignettes and social encounters. As the scenes accumulate and the tension rises (the pacing is maniacally steady without being monotonous), gang warfare and political persecution culminate in a heedless, pointless knifing. I spoil you no spoiler, as the film’s Chinese title translates as “The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street.” In the course of the action, the film becomes an elegy to the ideals and errors of adolescence, a probing of the vanities of the male ego, a reflection on the pain of emigration, and a critique of social repression.

Starting from an actual incident doubtless recalled by some of the 1991 audience, A Brighter Summer Day builds out into what Yang called “a picture of an age.” The whole film, a magnificent piece of plot architecture, balances concrete individuality, as each character comes to vivid life, with a sense of how all fit into larger socio-political dynamics of one historical moment. Yet the characters aren’t mere place-holders or mouthpieces; they can surprise us by not behaving according to type. The well-off son of a general protects other boys from bullying, while the gang leader Honey, on the run for murder, turns from violence after reading War and Peace.

With this film Yang asserted himself as the equal to Hou Hsiao-hsien. Together, they lifted their nation’s filmmaking to world stature. You need only watch Criterion’s bonus documentary on Taiwanese New Cinema to see how, in about ten years, a sincere but somewhat patchwork local trend gained force, polish, and precision. In Hou’s films of the 1980s, from The Boys from Fengkuei (1983) and Summer at Grandfather’s (1984) to the masterpiece City of Sadness (1989), a modest regional realism grew into a monumental effort at historical understanding and cinematic innovation. Yang was doing the same in his own way, and A Brighter Summer Day became his response to Hou’s lyrical epic.

Two ways, at least, to be modern

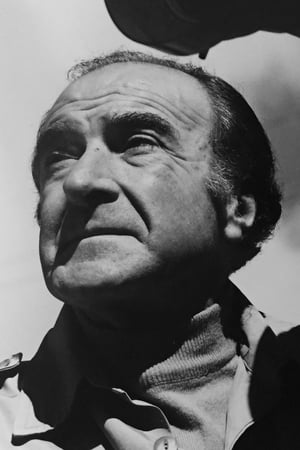

Edward Yang Dechang.

The new generation of Taiwanese directors faced a local cinema divided between commercial genres (action, melodrama, romantic comedy) and government-sponsored “healthy realism” promoting a bucolic, idealized rural life. Like the Italian Neorealists, the New Taiwanese Cinema sought a more humanistic realism. The new films told humdrum but heartfelt stories using non-actors and deglamorized locations.

In this context, the ambitions of Edward Yang stood out sharply. While in America to work as a computer engineer, he dropped in and out of film schools. Returning to Taiwan to make a successful TV film, he began to explore contemporary life in his country through the forms made famous by Resnais, Antonioni, and their successors. He became Taiwan’s most Europeanized modernist.

The intricacies of That Day, on the Beach (1983) make other New Taiwanese Cinema films look rough-hewn. A concert pianist on tour meets her old school friend, and they talk over their lives. The pianist turns out to be a secondary character in a three-hour exploration of growing up and finding a career in contemporary society. There’s a mystery—the friend’s husband has vanished, perhaps by suicide—but, as in L’Avventura, the disappearance sends out ripples that reveal social pressures and psychological states. There are flashbacks, both fragmentary and extended; there are flashbacks within flashbacks; there are multiple narrators, replays of key events, and floating voice-overs—all in the service of probing the ways in which patriarchal authority stunts young people’s lives.

That Day, on the Beach is an essential film of its period and place, but unavailable in good video copies, as far as I know. Its revival is another task for Film Culture, Inc. to take up.

Taipei Story (1985) is more focused, but it reiterates Yang’s interest in parallel lives and parental control. The milieu would become Yang’s distinctive territory: modern corporate culture and its wearing away of local traditions and family ties. A couple are torn apart by the man’s loyalty to the woman’s profligate father, while she falls into a perfunctory round of flirtations. The couple talk of marrying and starting over in America, but the man, an inarticulate loser steeped in old-school business practices, can’t cope with the new world of clever executives, discos, and hooking up.

Yang came to festival attention with The Terrorizers (1986), one of the most experimental films of the New Cinema. It’s a network narrative, in which jerky coincidences connect a Eurasian girl, a doctor, a photographer, a policeman, and a novelist starting her new project. The nearly opaque opening presents a police raid in a jagged montage capped by a voice-over: “It was the first day of spring.” Thereafter it’s up to us to sort out the tangled connections, provoked by the Eurasian girl randomly phoning strangers to stir up trouble.

Once more Yang takes on male inadequacy, as the novelist’s husband becomes estranged from her and she launches an affair with a coworker. And once more Yang shows the individual succumbing to demands of the business world—not only the novelist’s office work but also the husband’s scramble to win a higher post in his hospital. Two final bloodbaths, one imaginary, counterbalance the opening.

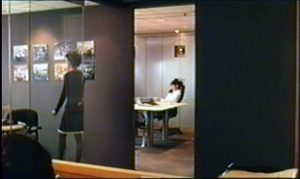

Across these three features, Yang’s technique grew ever more polished. In filming company offices, he adroitly used windows and partitions to emphasize mistrust (Taipei Story, below left) and bureaucratic ennui (The Terrorizers, below right).

The novelist’s office break-room in The Terrorizers is a sleek pod, while the photographer’s studio is rendered as a wraparound photomontage. In an echo of Blow-Up, his obsession with the Eurasian girl is presented in an outsize mosaic of stills.

Along with his compositional skill, Yang showed himself an editing-oriented director. When the Eurasian girl limps out of the gun battle, she collapses on the sidewalk in three planimetric shots. The staccato images could almost be comic-book panels; Yang was an adept cartoonist.

A later pair of shots recalls the sequence. Yang often relies on stylistic repetitions to bind up an elliptical, degrees-of-separation plot.

In all these respects, Yang became something of a counterweight to Hou. Both were social realists, but they worked in competing domains. Hou tended to concentrate on life in the countryside, or on rural characters transplanted, bewilderingly, to the city. His tranquil style favored a reflective mood and muted emotion. His reliance on long takes, telephoto framings, static camera, and simple editing patterns (the axial cut-in being a favorite) made him appear in harmony with other New Cinema directors. By contrast, Yang probed yuppie life in cinematic terms that seemed more sophisticated and up-to-date.

Actually, Hou was forging an innovative style that owed little to 60s modernism. He relied on minute changes in lighting and staging within the distant, packed, fixed long take. We find this style emerging in his early commercial features, becoming refined in his New Cinema projects, and, in Dust in the Wind (1986) and Daughter of the Nile (1987), constituting a rich continuation of cinema’s tableau tradition. Hou’s work became a prime example of what came to be considered “contemplative cinema” and “Asian minimalism.” City of Sadness (1989) made this “neoprimitivism” (the phrase is Tony Rayns’) starkly apparent, as it blended with network-narrative plotting and an exceptionally oblique approach to exposition. Filmmaking has not been the same since.

Hou and Yang were exact contemporaries, both born (like me) in 1947. They had been friends and collaborators; Hou played the protagonist of Taipei Story, while Yang helped Hou with the score of The Boys from Fengkuei and took a role in Summer at Grandfather’s. They separated, as Yang did from nearly all his New Cinema comrades.

Given the importance of competition in artistic milieus, it’s not too much to suggest, as Tony Rayns does in the Criterion commentary, that the commercial and critical success of City of Sadness prodded Yang to boost his game. He too would launch a critical probing of his roots and of Taiwan’s past; he too would create a vast ensemble film. He would shift from office politics to real politics. And he would absorb and rework aspects of Hou’s style.

Backing off, stepping aside

A while back I distinguished between “stubborn stylists” like Bresson and Tati, who cling to their preferred techniques through thick and thin, and adaptable ones who modify their approach as broader norms change. The early films of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni were indebted to a deep-focus style, but late in their careers they began to rely on the pan-and-zoom techniques that became widespread in the 1960s and 1970s.

There’s another possibility, though. You the filmmaker can try out your rival’s methods, but then push them in directions that extend your own inclinations. The result can refresh your films and become part of your creative toolkit for future projects. This is what I think Yang did in A Brighter Summer Day.

Begin at the beginning. The opening moments introduce the rules, the intrinsic norms, of Yang’s film. During the credits, a hanging lightbulb is switched on.

Pulsating light becomes a multivalent motif throughout the film, carried via a flashlight, abrupt power cuts, and in a climax some hours later, a lightbulb smashed by a baseball bat.

As the credits continue, a flagrantly uninformative extreme long shot shows a man pleading with an unseen educator. He’s complaining about his son’s grades and asking about the boy’s transfer to a night school. Who is he? In probably the most unemphatic introduction of a protagonist in Taiwanese cinema, we get another extreme long shot of the boy we’ll come to call Si’r, waiting outside.

It’s Kuleshov constructive editing at work. There’s no long shot establishing the two spaces, nor can we assume that the first shot is, retrospectively, Si’r’s optical POV. But Kuleshov, who cared about punchy clarity, could hardly have approved of the far-off, information-stingy framings. Throughout the film we’ll see doorways block off parts of the action, extremely distant views frame a few scrubby figures, and shots dwelling on empty zones. This opening teaches us how to watch the movie.

Another rule: what Emilie Yueh-Yuh Yeh and Darrell William Davis call the tunnel-vision composition. This template is introduced in a perspective shot that waits ninety seconds for father and son to come to the foreground.

This first pair of scenes sets the task: We must suspend our craving for backstory and let the filmic narration slowly parcel out what we need to know—while still leaving a good deal to inference and imagination. Even more than Yang’s elliptical 1980s films, this is observational cinema, but with characters set at more than arm’s length.

Immediately, again with no establishing shot, we finally get a look at Mr. Zhang and Si’r seated at a food stall. Characterization is starting already, as we see the fretful father snuff out his cigarette and carefully save the butt. Much later he’ll quit smoking to save money.

Throughout, Yang will occasionally embed medium shots and closer views like these into his wide framings, anchoring his characters enough for recognition and revelation but not enough for the heated-up empathy encouraged by mainstream filmmaking. At various points, he will resort to shot/reverse shot as an accent within a more opaquely filmed scene.

These first few moments show how Yang has modified Hou’s signature devices. The shots seem poised between Yang’s earlier work and Hou’s tableau frames. Here the long shots tend to be either more distant or closer than Hou’s; Hou seldom uses the steep central-perspective imagery we see throughout Yang’s film; nor does Hou rely on the simple, straightforward medium shots we see in the food stall. Yang is, I think, blending his own inclinations with some tendencies revealed to him by City of Sadness and other films.

As if to push Hou’s preferences further, Yang stages many scenes with the camera set very far off. And instead of using a long lens to supply a frieze effect, with packed-in bodies shifting slightly this way and that, Yang’s frames are open and porous, though pocked with holes and streaked with shadow regions.

He will hold on frames devoid of human presence; as with Antonioni, a scene begins a bit before it begins and ends a bit after it ends.

One result is that “dedramatization” so prominent in postwar European art cinema. Even gang fights and deadly chases are observed with a dryness and detachment that allows us to appraise the action coolly. Yang’s shadowy, distant shots are the main reason you need to see this film on the biggest screen you can wangle. The first gang rumble and our initial sight of the family at dinner need scale to be legible. (Sorry I must post them so small.)

A major benefit of Hou’s dense staging is an emphasis on what I call his “just-noticeable differences.” Tiny shifts in character position reveal a detail to us, or pry open a view of something further back. Yang’s more open frames don’t exploit this as much. The frame at the top of today’s entry is a good example, with the heads spotted in the frame as a good cartoonist would.

In Hou’s City of Sadness, a scene of a gang confrontation is handled through tight timing and JND head-shifting that teasingly reveals facial expressions.

In A Brighter Summer Day, the wonderful scene of Honey’s return and Sly’s attempt to take over the gang is staged in a free lateral flow, with Cat scrambling into the frame again and again to break up the fight. Yang orchestrates bodies and faces for maximum clarity, moment by moment.

That horizontal staging is nicely broken by crucial movements along the lens axis, as first Ming and finally her boyfriend Honey come out from the area behind the camera and plunge into depth. The camera tracks gravely forward following him as he asserts his command.

There’s almost none of the blocking-and-revealing tactic that Hou relies upon. Yang’s framings are grave and spacious. More pragmatic than Hou, he’s willing to build the drama in a clear-cut fashion–as befits a director who sought to train a new generation of actors and who staged plays between his film projects. In this movie, I think, Yang found a middle way between his more disjunctive early style and Hou’s dense, blocklike tableaus.

Further evidence of this middle way is Yang’s revised attitude toward editing. Each of his 1980s films, while not subscribing to Hollywood’s frantic intensified-continuity principles, is built out of a great many shots. By contrast, the four hours of A Brighter Summer Day consist of only about 520 shots, averaging about 28 seconds each. The film contains several long takes and many single-shot scenes, so here we find him trying out the Hou approach. But as in the opening school sequence and the stall meal, editing does come into play during some tense conversations, notably when Si’r’s father is undergoing police interrogation.

As at the start of Terrorizers, editing can occlude one crucial bit of action. What happened in that schoolroom during the gang raid? Yang’s choppy cuts respect the mere glimpse that Si’r gets of the boy and the girl who fled the room when he switched on the light.

In such passages, Yang’s abrupt cutting creates accents that break the attenuated, adagio rhythm of long, usually static shots. Here it adds to a central mystery of the film as well.

The elusive implications of the compositions and cuts are writ large in the film’s narrative rhythm. Here Tony Rayns’ magnificent commentary illuminates Yang’s artistry. Much of the story relies on local knowledge of Taiwanese culture, and Yang does not provide it in any direct way. Tony shows that every scene carries a historical and social subtext.

Just as important, story premises aren’t always spelled out; we’re expected to connect many dots. For example, nobody explains that Si’r’s eyesight is failing, and that he swipes the film studio’s flashlight so he can read more easily in his cramped bedroom. But because of his imperfect vision, he is getting injections of medicine, which take him to the school clinic and then to encounters with Ming and the doctor treating her. And Si’r’s father eventually toys with the possibility of buying him glasses on the installment plan (though then he’d have to economize by giving up cigarettes). Another film would have made a dramatic issue of Si’r’s vision problem; here, these story elements enter on the fringe of other dramatic action, mingle with other elements, and must be linked together by the alert viewer.

The result is that story motifs—the light bulb, the flashlight, the mother’s watch, a samurai sword, a vagrant snapshot, rock-and-roll tunes, baseball bats—don’t simply repeat across the film but rather mingle and overlap. Tony speaks of “resonances”; we could as easily talk of “ramifications.” Each prop or incident radiates in several directions, becoming a node in several plot lines. The dots we connect fuse in a multidimensional space. The strategy has affinities to Yang’s earlier films, but in none of them do we have this spacious dramatic density.

The film needs its four hours to develop all these motifs and to render events and milieus as gradually changing. The strongest example of this stepped development is Si’r’s “character arc,” which is rendered in a host of small moments, often treated indirectly or elliptically. Characteristically for Yang, as the climax approaches, our protagonist slips away from us—seen from the rear, kept offscreen, and ultimately as alone in a vast long shot as he had been at the beginning, but now turned steadfastly from us, as if defying us to understand and sympathize.

A Brighter Summer Day enabled Yang to absorb some stylistic extremes that were initially alien to him. He could find his versions of the distant, hard-to-read shot, without abandoning his commitment to more direct access to character reaction. Over-neat as it sounds, I’d argue that after trying out the Hou-ish options, he arrived at a new synthesis in his last three features. Two more social satires, A Confucian Confusion (1994) and Mahjong (1996), return to the cosmopolitan terrain of the early features. Now, however, there’s nothing so off-puttingly remote as many scenes in A Brighter Summer Day.

Chaplin said that comedy demands long-shot while tragedy lives in close-up. Yang begs to differ somewhat. A Brighter Summer Day gives us pathos in extreme long shot, but A Confucian Confusion yields comedy in mid-shot. Admittedly, however, those oblique doorways do their bit in mocking yuppie pretensions.

A Confucian Confusion closes with a nifty elevator shot displaying an easy command of classical staging.

Yang’s most widely-seen film Yi Yi (A One and a Two, 2000) shows the same synthesis at work for dramatic rather than comic purposes. Again, recurring locales and threaded motifs sustain a network tale anchored in family, neighborhood, and workplace. The familiar Yang clash of personal impulse and corporate corruption plays out in the cozy spaces of a household and the gridded confines of business hotels, company headquarters, and hospitals.

If Yi Yi seems to me a less daring film than A Brighter Summer Day, perhaps it’s because Yang has decided to work in a more traditional arthouse vein. For the first time in a Yang film, a child enters the mix. In the wake of Neorealism, many filmmakers realized that kids in movies can not only “defamiliarize” petty adult concerns; they can also attract audiences. But the presence of an unforgettable little boy shouldn’t be taken as a concession to international tastes. Little Yang’s camera-hound alertness adds a perspective that evokes the forbidding, oblique setups of A Brighter Summer Day: people with heads turned from us.

Edward brings his namesake into the plot comparatively late, to serve as a kind of observer and spokesman. “I want to tell people things they don’t know,” Yang Yang says at his grandmother’s funeral. “Show them things they haven’t seen.” It could be an epigraph for A Brighter Summer Day.

Thanks to Tony Rayns, as well as Curtis Tsui, Kim Hendrickson, and Peter Becker of Criterion. The best sustained discussion of Yang’s films I know is in the third chapter of Emilie Yueh-Yuh Yeh and Darrell William Davis’ Taiwan Film Directors: A Treasure Island (Columbia University Press, 2005).

Since its second edition of 2003, our textbook Film History: An Introduction has included extensive discussions of Hou, Yang, and New Taiwanese Cinema. I’m proud that we gave attention to these filmmakers when other world cinema surveys ignored them. I discuss Hou’s style at length in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging and in these web entries. There’s a sidebar on A Brighter Summer Day in the book as well.

I met Edward a couple of times in the 1990s, most memorably at the Kyoto Film Festival. I’ll always remember him pedaling his rented bike around town but always ready to have a meal and talk about the films he loved.

I wrote a valedictory on Edward’s death here. Today’s entry picks up a couple of points made there.

P. S. 28 June 2016: Thanks to Carman Tse for correction of my spelling of the family’s name. Carman points out that the protagonist’s proper name is Chang Chen, the same as the actor’s own name. (“Chang” is a common Westernization for “Zhang,” the family’s name.) Carman adds, as I should have, that Xiao Si’r means “Little Fourth Son,” a point also made in Tony Rayns’ commentary and Godfrey Cheshire’s liner essay. Because the subtitles, Tony’s commentary, Godfrey’s essay, and much critical writing on the film refer to the boy as Xiao Si’r, for the sake of consistency that’s the one I’ve retained in the piece.

Ultimately It's All True aborted and RKO proceeded to edit the film from Welles' reduced 131 minutes to 88 minutes, including the insertion of the hospital scene at the end. This scene had not been written by Welles and was directed by Freddie Flick and scored by Roy Webb, instead of Bernard Herrmann whose haunting score is so essential a part of the film.

Ultimately It's All True aborted and RKO proceeded to edit the film from Welles' reduced 131 minutes to 88 minutes, including the insertion of the hospital scene at the end. This scene had not been written by Welles and was directed by Freddie Flick and scored by Roy Webb, instead of Bernard Herrmann whose haunting score is so essential a part of the film.

Paramount to the success of Ambersons is the excellent acting. Tim Holt as George. ["Holt’s intense concentration on what another character says, you can see all of George’s calculations reflected: 'What does this have to do with me? How do I benefit?'--Farran Smith Nehme, TCM]

Paramount to the success of Ambersons is the excellent acting. Tim Holt as George. ["Holt’s intense concentration on what another character says, you can see all of George’s calculations reflected: 'What does this have to do with me? How do I benefit?'--Farran Smith Nehme, TCM] Cotten capturing Welles’s own ambivalence [towards his invention] in the wonderful dinner scene where the relentlessly antagonistic George viciously insults him and his automobile, while Eugene responds not with understandable anger or resentment but with quiet affability, concession: he agrees with George, expressing his own reservations about the invention and what it will do to humanity. We never know what technology will do and how it will change us, he says, and he might be talking about the electronic inventions of a century later.

Cotten capturing Welles’s own ambivalence [towards his invention] in the wonderful dinner scene where the relentlessly antagonistic George viciously insults him and his automobile, while Eugene responds not with understandable anger or resentment but with quiet affability, concession: he agrees with George, expressing his own reservations about the invention and what it will do to humanity. We never know what technology will do and how it will change us, he says, and he might be talking about the electronic inventions of a century later.

[About that sentimental tacked-on ending,] it isn’t even close to the ending of Welles’s own bleak design, shot by the director [A shot of which is above, released by RKO for promotional purposes.] and thought by him to be the best scene in the film. (Though the studio version is arguably a little closer to the brush-with-the-supernatural conclusion of the Booth Tarkington novel.)

[About that sentimental tacked-on ending,] it isn’t even close to the ending of Welles’s own bleak design, shot by the director [A shot of which is above, released by RKO for promotional purposes.] and thought by him to be the best scene in the film. (Though the studio version is arguably a little closer to the brush-with-the-supernatural conclusion of the Booth Tarkington novel.)In the re-shot ending, Eugene Morgan speaks to Fanny Minafer as they walk down a hallway towards the cameras. It’s played pretty straight, as Eugene reveals he has reconciled with George.